People who

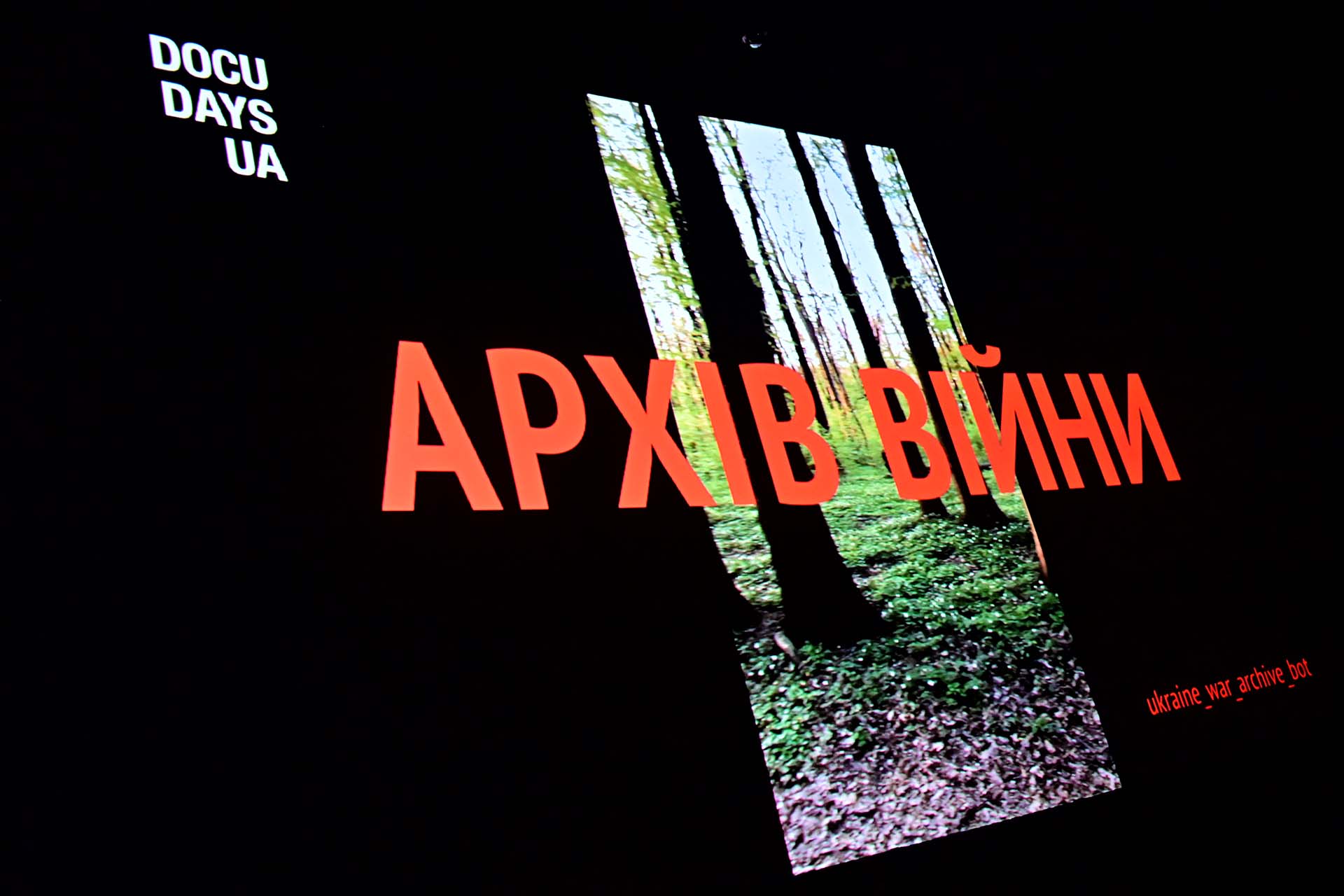

Maria Buchelnikova is a project manager of Ukraine War Archive, one of the key directions of the Docudays NGO. The team has gathered more than 3100 hours of war crimes testimonies and witness interviews.

Docudays became one of the first NGOs supported by the House of Europe. The Docudays team formed the project concept in March 2022. In April, the British organisation Infoscope joined the project's development, and since May, they began the active phase of work. They moved from an encyclopedia concept highlighting the fundamental aspects of the war to the idea of an archive. The project supports all formats, tries to record as many events connected to the war as possible, and cooperates with the media and human rights organisations.

We spoke with Maria about the importance of documenting the war. She explained why it is essential to download content from the Russian propaganda channels, why the archive has three levels of access, and how materials from the archive can help to hold Rrussians responsible.

Docudays became one of the first NGOs supported by the House of Europe. The Docudays team formed the project concept in March 2022. In April, the British organisation Infoscope joined the project's development, and since May, they began the active phase of work. They moved from an encyclopedia concept highlighting the fundamental aspects of the war to the idea of an archive. The project supports all formats, tries to record as many events connected to the war as possible, and cooperates with the media and human rights organisations.

We spoke with Maria about the importance of documenting the war. She explained why it is essential to download content from the Russian propaganda channels, why the archive has three levels of access, and how materials from the archive can help to hold Rrussians responsible.

Maria Buchelnikova joined the Docudays team in the summer of 2021. At first, she worked as a communication manager. She was involved in the Travelling Docudays UA festival and the DOCU/CLUB film clubs.

The organisation's most famous project is International Human Rights Documentary Film Festival Docudays UA. It is held every March in Kyiv and features Ukrainian and international film programmes.

Travelling Docudays UA is a festival that travels to different regions of Ukraine with the programme of Kyiv Docudays UA to popularise documentary films and make them more accessible. Docuclub is another project by Docudays that anyone can join: people can register their own club and take documentaries from the media library. Besides giving access to the films, Docudays provides help in the moderation of discussions to the clubs, educates about human rights and teaches how to conduct human rights events.

After 24 February 2022, Ukraine War Archive became one of the strategic directions of Docudays.

‘The whole Docudays team came up with this project in March, Maria Buchelnikova, the project manager, says.

The organisation's most famous project is International Human Rights Documentary Film Festival Docudays UA. It is held every March in Kyiv and features Ukrainian and international film programmes.

Travelling Docudays UA is a festival that travels to different regions of Ukraine with the programme of Kyiv Docudays UA to popularise documentary films and make them more accessible. Docuclub is another project by Docudays that anyone can join: people can register their own club and take documentaries from the media library. Besides giving access to the films, Docudays provides help in the moderation of discussions to the clubs, educates about human rights and teaches how to conduct human rights events.

After 24 February 2022, Ukraine War Archive became one of the strategic directions of Docudays.

‘The whole Docudays team came up with this project in March, Maria Buchelnikova, the project manager, says.

The full-scale invasion put many projects on pause. So we tried to figure out what to do next: how to reformat our work according to current needs and how we could help. There was a massive stream of videos on Telegram channels at that moment: from frontline footage to funny videos about people stealing tanks. Videos like that get lost and forgotten quickly, so we thought: ‘Perhaps, we can save them somehow?

At first, the project was supposed to be in the encyclopaedia format: the chronicles of the war that people recorded, or at least some part of it. Then, the idea transformed into an archive that would store everything to document the war in the most detailed way possible.

Why we need a legal framework and partnerships

Ukraine War Archive concept suggested that the team would search for, save, and tag the materials to make a catalogue. In fact, it is a database with the feature of keywords search: date, location, and the key characteristics of the event.

Maria and the team studied a lot of existing digital archives and how they were created. That was when they discovered that many video materials filmed or streamed during Euromaidan in 2013-2014 had disappeared. That was probably because the storage period on the servers had expired.

Some interviews with Euromaidan participants survived, but the authors did not prepare a legal framework and did not get permission for public use of the content. Due to that, these interviews cannot be published now.

Why we need a legal framework and partnerships

Ukraine War Archive concept suggested that the team would search for, save, and tag the materials to make a catalogue. In fact, it is a database with the feature of keywords search: date, location, and the key characteristics of the event.

Maria and the team studied a lot of existing digital archives and how they were created. That was when they discovered that many video materials filmed or streamed during Euromaidan in 2013-2014 had disappeared. That was probably because the storage period on the servers had expired.

Some interviews with Euromaidan participants survived, but the authors did not prepare a legal framework and did not get permission for public use of the content. Due to that, these interviews cannot be published now.

Some of the interviewees are not alive anymore. Some of them are impossible to contact. So, unfortunately, videos like that remain a dead weight in folders as no one can use them due to legal regulations. Or one will be able to use them in the future when the statute of limitations expires, and it will be impossible to sue people or violate their rights and safety. But this will not happen soon.

The Ukraine War Archive team gets permission to save the materials and hand them over to human rights organisations, courts, the prosecutor's office, or the police from the authors of the videos. They also plan to start getting permission for public use.

At first, they wanted to gather only the materials sent by people and created a Telegram bot for that. But people are not always up to it because it does not look trustworthy enough. That is why Docudays started partnering with other initiatives.

‘Calling the project “Ukraine War Archive” is a very ambitious thing to do, Maria Buchelnikova says. We must live up to this name and make the picture as bright and comprehensive as possible. There are a lot of similar projects right now, but we understand that competition will do no good. On the contrary, we need to become partners. We can make each other stronger and gather more information.’

The project’s partners are the National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide, Ukraїner media, Suspilne, Hromadske, Ukrainian Witness documentary project, Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union, Center for Civil Liberties and others.

The team’s aim is not only to record the war events but also to document the war crimes. So the project participants had discussions with human rights organisations on how to collect testimonies of people affected by the war. And they decided to help gather information that could be useful for research and investigations.

At first, they wanted to gather only the materials sent by people and created a Telegram bot for that. But people are not always up to it because it does not look trustworthy enough. That is why Docudays started partnering with other initiatives.

‘Calling the project “Ukraine War Archive” is a very ambitious thing to do, Maria Buchelnikova says. We must live up to this name and make the picture as bright and comprehensive as possible. There are a lot of similar projects right now, but we understand that competition will do no good. On the contrary, we need to become partners. We can make each other stronger and gather more information.’

The project’s partners are the National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide, Ukraїner media, Suspilne, Hromadske, Ukrainian Witness documentary project, Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union, Center for Civil Liberties and others.

The team’s aim is not only to record the war events but also to document the war crimes. So the project participants had discussions with human rights organisations on how to collect testimonies of people affected by the war. And they decided to help gather information that could be useful for research and investigations.

We are looking for witnesses and collecting their stories. We have a network of interviewers who record the testimonies. We have developed certain legal documents with permissions and instruction guides on conducting interviews and collecting testimonies. In addition to that, we have developed a classification of war crimes. There are many of them: both crimes against humanity and war crimes. For now, we use the classification of war crimes by the Rome Statute, but maybe we will expand it.

What is in the archive, and how to get access to it

Ukraine War Archive is a joint database of the war chronicles with the materials gathered from different organisations. They receive safe preservation, cataloguing, archiving, verification, and access to the content.

‘At first, we wanted to collect only audio and video. However, audio materials are more problematic because they are more intimate: voice messages on Telegram and audio diaries. People usually do not share such things,’ Maria explains.

The technical base of the archive, developed by the British organisation Infoscope, can save not only video but all kinds of files: documents, scanned documents, etc. That is why there are also interviewers’ notes and photo diaries of the witnesses.

‘There is no censorship as such, but we try to check whether there is common sense in the materials, Maria Buchelnikova says. Because, for example, there were people with the nickname Zelenskyy*#*?#!?* who would send spam.

We sort out all the materials we receive from third parties: look through them and upload them into the archive. Then our specialists review them and add tags.

We also want to add verification because there are materials that can be fake. For example, no one prevents the Russians from uploading videos discrediting the Ukrainian military or the authorities. There is no guarantee that what we see in a video is what is actually going on. Such materials demand a more careful professional check.’

The team does not add materials that violate the law to the archive. However, according to Maria, this parameter is constantly changing: today, videos with the movement of the Armed Forces of Ukraine cannot be published, but in a month, when our soldiers are not there anymore, such videos do not pose an actual threat. So this does not limit the choice.

At the end of 2022, Ukraine War Archive collected 350+ hours of sorted and at least partially tagged video materials, 120+ hours of interviews with war crimes witnesses. and almost 900 hours of videos from open Telegram channels. And those numbers are constantly growing.

Ukraine War Archive is a joint database of the war chronicles with the materials gathered from different organisations. They receive safe preservation, cataloguing, archiving, verification, and access to the content.

‘At first, we wanted to collect only audio and video. However, audio materials are more problematic because they are more intimate: voice messages on Telegram and audio diaries. People usually do not share such things,’ Maria explains.

The technical base of the archive, developed by the British organisation Infoscope, can save not only video but all kinds of files: documents, scanned documents, etc. That is why there are also interviewers’ notes and photo diaries of the witnesses.

‘There is no censorship as such, but we try to check whether there is common sense in the materials, Maria Buchelnikova says. Because, for example, there were people with the nickname Zelenskyy*#*?#!?* who would send spam.

We sort out all the materials we receive from third parties: look through them and upload them into the archive. Then our specialists review them and add tags.

We also want to add verification because there are materials that can be fake. For example, no one prevents the Russians from uploading videos discrediting the Ukrainian military or the authorities. There is no guarantee that what we see in a video is what is actually going on. Such materials demand a more careful professional check.’

The team does not add materials that violate the law to the archive. However, according to Maria, this parameter is constantly changing: today, videos with the movement of the Armed Forces of Ukraine cannot be published, but in a month, when our soldiers are not there anymore, such videos do not pose an actual threat. So this does not limit the choice.

At the end of 2022, Ukraine War Archive collected 350+ hours of sorted and at least partially tagged video materials, 120+ hours of interviews with war crimes witnesses. and almost 900 hours of videos from open Telegram channels. And those numbers are constantly growing.

The archive has three levels of access.

The first level is for the materials from open sources or the media, which are already available. But they are systematised and tagged in the archive.

The second level is for the materials sent directly by people and partners or materials containing personal information: a face or voice.

The third level is for the most sensitive materials, interviews with people who suffered torture or violence. Only human rights organisations and lawyers have access to them.

Access to the archive is closed to the public. You cannot just get or find the link. For security reasons, the team decided it would be this way, at least until the end of the war.

‘For now, we only give access to the archive to trusted people: by request from the people we know or from a close circle of the organisations, Maria explains. First, we ask them to fill in the application and explain why they need access. After that, we sign an agreement.

The thing is, personal information is not only name, surname and address but also face and voice. So we cannot endanger people who were interviewed or sent us a video.’

The first level is for the materials from open sources or the media, which are already available. But they are systematised and tagged in the archive.

The second level is for the materials sent directly by people and partners or materials containing personal information: a face or voice.

The third level is for the most sensitive materials, interviews with people who suffered torture or violence. Only human rights organisations and lawyers have access to them.

Access to the archive is closed to the public. You cannot just get or find the link. For security reasons, the team decided it would be this way, at least until the end of the war.

‘For now, we only give access to the archive to trusted people: by request from the people we know or from a close circle of the organisations, Maria explains. First, we ask them to fill in the application and explain why they need access. After that, we sign an agreement.

The thing is, personal information is not only name, surname and address but also face and voice. So we cannot endanger people who were interviewed or sent us a video.’

What awaits Ukraine War Archive this year

Now, Ukraine War Archive is filling up even with the materials from open Telegram channels: the technical team set up an algorithm that uploads videos on its own. They not only take videos from Ukrainian sources but also collect Russian propaganda materials.

‘It is not for the sake of balance because there cannot be one. It is to show what nonsense our enemy tells about us, how they manipulate their audience, what propaganda they share, Maria explains. In the future, it can be helpful in historical or art research.

It would be good to involve the analytical department to look for interesting connections there and study Russian war propaganda.’

The team thinks about what other content they can add to the archive. Among the options, they consider collecting materials from those Ukrainians who left the country because their experience is also a part of the war. It can include, for example, videos from the protests or other events aimed at drawing foreigners’ attention.

Ukraine War Archive also plans to become partners with foreign media. Even though their editorial offices are not in Ukraine, many journalists come and film.

‘Of course, they often show the war not the way we would like them to, but this is also a part of the whole picture,’ Maria clarifies.

And also, in the plans for 2023, there is a review of the team structure. We want to find more taggers because they work with a large amount of information, interaction with which can sometimes be emotionally challenging.

‘We want to conduct a few training sessions on working with stress and fatigue. Now we are looking for a partnership with an organisation that provides psychological support so that our team members, especially interviewers and taggers, can consult psychotherapists.

We imagine that one day our archive can become a digital museum with open access. However, we will see for how long we can support it technically because I cannot imagine what will happen to the digital museum in 20 years.’

Now, Ukraine War Archive is filling up even with the materials from open Telegram channels: the technical team set up an algorithm that uploads videos on its own. They not only take videos from Ukrainian sources but also collect Russian propaganda materials.

‘It is not for the sake of balance because there cannot be one. It is to show what nonsense our enemy tells about us, how they manipulate their audience, what propaganda they share, Maria explains. In the future, it can be helpful in historical or art research.

It would be good to involve the analytical department to look for interesting connections there and study Russian war propaganda.’

The team thinks about what other content they can add to the archive. Among the options, they consider collecting materials from those Ukrainians who left the country because their experience is also a part of the war. It can include, for example, videos from the protests or other events aimed at drawing foreigners’ attention.

Ukraine War Archive also plans to become partners with foreign media. Even though their editorial offices are not in Ukraine, many journalists come and film.

‘Of course, they often show the war not the way we would like them to, but this is also a part of the whole picture,’ Maria clarifies.

And also, in the plans for 2023, there is a review of the team structure. We want to find more taggers because they work with a large amount of information, interaction with which can sometimes be emotionally challenging.

‘We want to conduct a few training sessions on working with stress and fatigue. Now we are looking for a partnership with an organisation that provides psychological support so that our team members, especially interviewers and taggers, can consult psychotherapists.

We imagine that one day our archive can become a digital museum with open access. However, we will see for how long we can support it technically because I cannot imagine what will happen to the digital museum in 20 years.’

How House of Europe helped the project

House of Europe started supporting Ukraine War Archive last spring. Ilona Demchenko, a programme manager of the organisation, says that they decided to help the project as soon as they heard about it:

‘Docudays is an organisation with a perfect reputation. We knew about their activity and that they are reliable partners. At first, they turned to the representation of the European Commission in Ukraine. and the colleagues passed the project to us.

In a time when we couldn’t hold open calls as we normally do, but were scouting for initiatives in need as they emerged, it was clear that the request was essential and urgent. We were glad to support the project because we understood that the idea is of great significance both for the culture and future investigations.’

Maria says that House of Europe is a recurring partner of their organisation.

‘The programme supported Ukraine War Archive when the project only started when we could not yet show results, she says. And it is very cool because it is a question of trust and confidence: we will do what we have promised. We will use this money efficiently and honestly. They gave us quite a powerful boost.’

House of Europe supported the project from May to September 2022. During this period, Docudays did the main load of work: added interview direction, involved partners, hired taggers, and developed agreements, guides, and first communication campaigns.

House of Europe started supporting Ukraine War Archive last spring. Ilona Demchenko, a programme manager of the organisation, says that they decided to help the project as soon as they heard about it:

‘Docudays is an organisation with a perfect reputation. We knew about their activity and that they are reliable partners. At first, they turned to the representation of the European Commission in Ukraine. and the colleagues passed the project to us.

In a time when we couldn’t hold open calls as we normally do, but were scouting for initiatives in need as they emerged, it was clear that the request was essential and urgent. We were glad to support the project because we understood that the idea is of great significance both for the culture and future investigations.’

Maria says that House of Europe is a recurring partner of their organisation.

‘The programme supported Ukraine War Archive when the project only started when we could not yet show results, she says. And it is very cool because it is a question of trust and confidence: we will do what we have promised. We will use this money efficiently and honestly. They gave us quite a powerful boost.’

House of Europe supported the project from May to September 2022. During this period, Docudays did the main load of work: added interview direction, involved partners, hired taggers, and developed agreements, guides, and first communication campaigns.

Our project can be useful for research, for a fight against propaganda in the future. After the victory, we will still have a lot of work in the information space to achieve justice. Russia will not get its influence back and will not get a chance to shout about how poor and miserable it is and how it also needs sympathy. We cannot let this happen. And the archive can become one of the tools in this fight.

Olha Vasina, photos from Ukraine War Archive and by Stas Kartashov, Maryna Roschyna and Alyona Lobanova

Back to main page